Cecil Talyor: A Museum For Sound

It is taken for granted the physical context in which a painting is hung. Vincent van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” (for recent observers) is synonymous with the Museum of Modern Art; the building, gallery style, floor plan, hordes of crowded patrons all contribute to the environment that forms the backdrop by which the art is experienced as a first hand, real time aesthetic interaction. Much like the canvas, frame, or negative space inside a piece, these elements help create a tangible and physical sense of place that is inseparable from the viewing of the physical object.The case of music is similar, although more mobile due to the nature of recorded media. But for whole genres of music a defined place, location, and space is essential. Swing bands had the Savoy Ballroom, bebop had its 52nd street and Minton’s, Hip Hop had Sedgwick Avenue, and Punk had its CBGBs.For Cecil Taylor, and indeed much of 1960s progressive jazz, the sense of location is missing from contemporary experience of the genre. Of course Taylor has performed on countless international stages for decades, but hasn’t been strongly associated with any in particular. With many of New York City’s famous 60s jazz incubators now long closed (The Village Gate, Slugs, The Take Three Coffee House, Tonic, and the most relevant incarnations of the Knitting Factory) the music of generation of musicians who pioneered the style now almost exclusively occupies spaces dominated by headphones, home stereos, computers, and personal listening environments. Location is absent as an essential and quiet frame around these artist’s output in the conciousness of those aquainted only with recorded sound.The recent installation at the Whitney Museum in NYC, “Open Plan: Cecil Taylor Apr 15–Apr 24, 2016” offered a stark reminder of what a space can contribute to the work of a musical artist, and what an abundance of space around the physical manifestations of that art can contribute to a fuller experience of its contents. For the work of an artist such as Cecil Taylor this presentation can be transformative. The concept of the open plan is:

…an experimental five-part exhibition using the Museum’s dramatic fifth-floor as a single open gallery, unobstructed by interior walls. The largest column-free museum exhibition space in New York, the Neil Bluhm Family Galleries measure 18,200 square feet and feature windows with striking views east into the city and west to the Hudson River, making for an expansive and inspiring canvas.

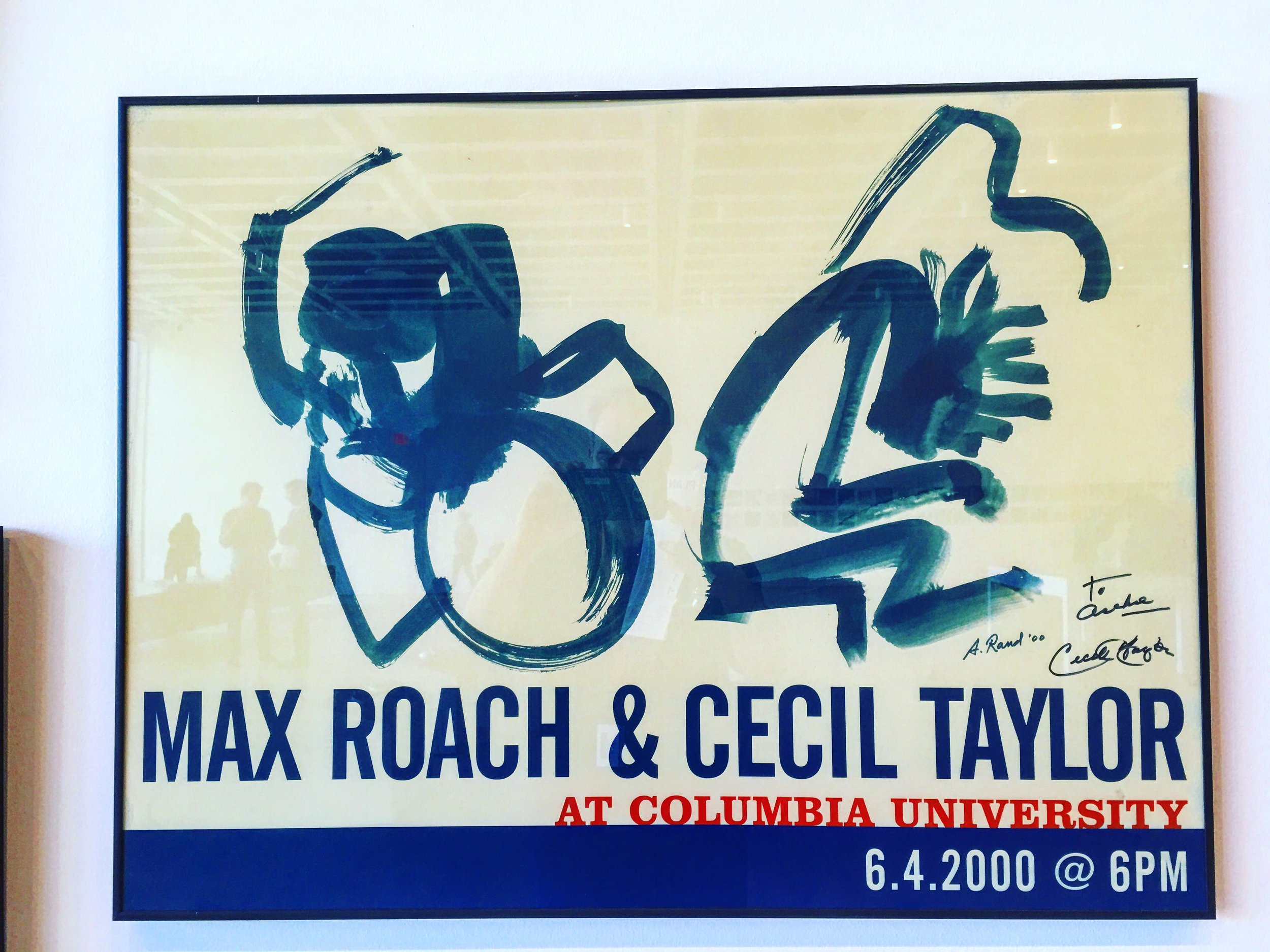

One was greeted in the expansive space by a massive angled projection screen playing Taylor’s performance from “Imagine the Sound”. The music and poetry emanating from the performance filled the space, which was dotted with countless music listeners, historians, experts on the era and the Black Arts Movement, and uninitiated Art enthusiasts who silently took in the displays filled with poetry notebooks, scores, concert posters, album covers, pictures, video screens, and memorabilia from Taylor’s 60+ year career. Drawn equally I imagine by the love of his work, or the ubiquitous curiosity to find out what he does, or perhaps why.

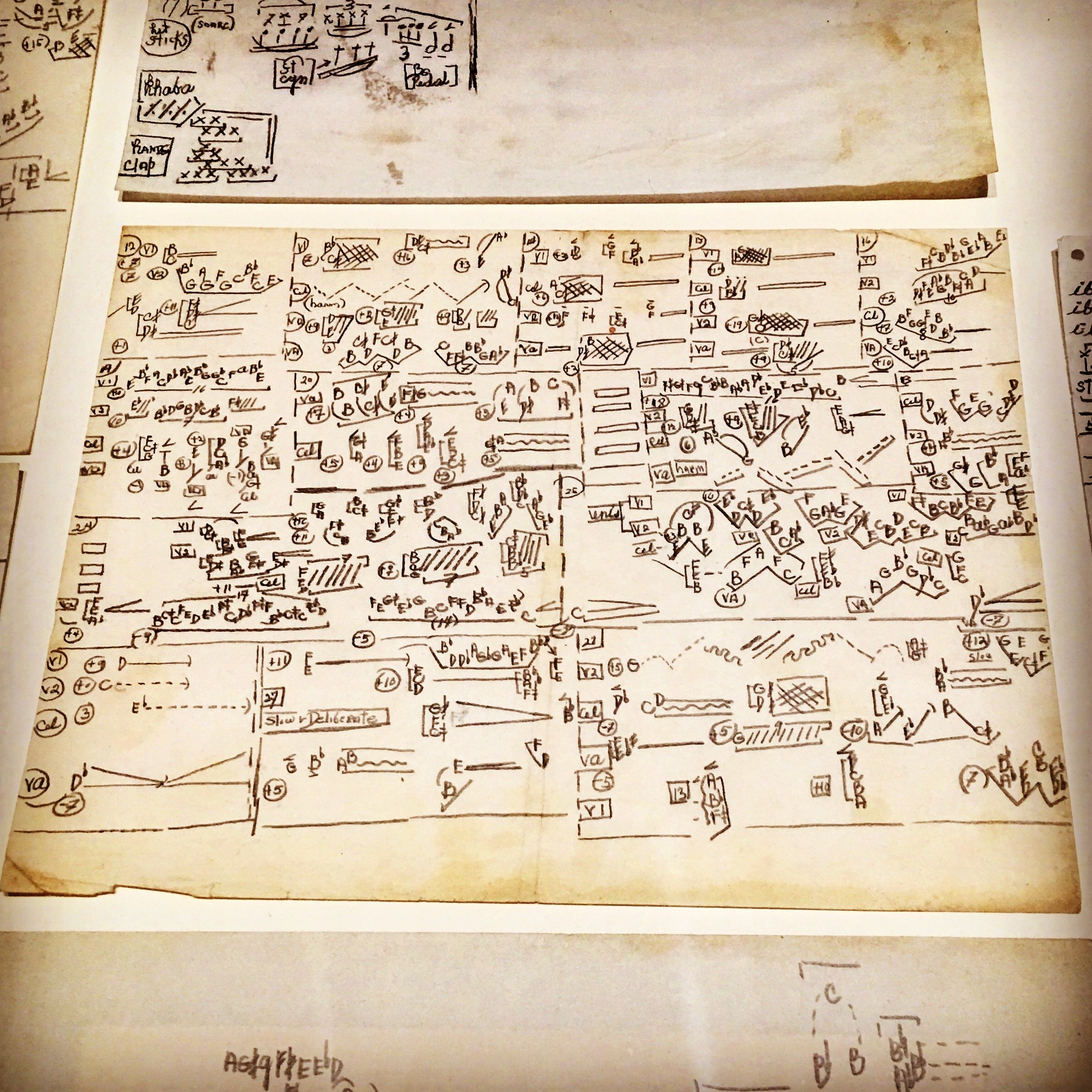

One was greeted in the expansive space by a massive angled projection screen playing Taylor’s performance from “Imagine the Sound”. The music and poetry emanating from the performance filled the space, which was dotted with countless music listeners, historians, experts on the era and the Black Arts Movement, and uninitiated Art enthusiasts who silently took in the displays filled with poetry notebooks, scores, concert posters, album covers, pictures, video screens, and memorabilia from Taylor’s 60+ year career. Drawn equally I imagine by the love of his work, or the ubiquitous curiosity to find out what he does, or perhaps why. One of the most striking elements where the countless scores under glass, which provided exacting detail into the visual elements Taylor has taken to the stage. Often indecipherable to those acquainted with standard notational practices, they show clumps of notes, intervals, gestures, and graphics that do an incredible job of representing the aural freneticism of many of his performances with an equaled visual energy and complexity.

One of the most striking elements where the countless scores under glass, which provided exacting detail into the visual elements Taylor has taken to the stage. Often indecipherable to those acquainted with standard notational practices, they show clumps of notes, intervals, gestures, and graphics that do an incredible job of representing the aural freneticism of many of his performances with an equaled visual energy and complexity. Despite the high-energy music that was being played over the house sound system, the space had a decided air of tranquility and focus, perhaps due to the un-crowded nature of each element of the exhibit. The Whitney did an admirable job in replicating the kind of aesthetic environment that facilitates interest, focus, and serenity around the musical objects as other museums can do around the work of visual artists. It was striking how a large group of people could be in one place learning about Cecil Taylor, and not in a performance venue listening to a concert. The space and presentation lent a dimension to Taylor’s work that seemed essential; a defined environment, surrounded by interested public, with enough physical space to explore the elements without feeling rushed. Curiosity was required, the act of walking up to something rather than having it be presented without warning completed the aesthetic transaction between listener and composer, the physical grandness of the space and the commitment needed to walk to each new corner seemed to make accessible even elements of Taylor’s output that seem to defy it.

Despite the high-energy music that was being played over the house sound system, the space had a decided air of tranquility and focus, perhaps due to the un-crowded nature of each element of the exhibit. The Whitney did an admirable job in replicating the kind of aesthetic environment that facilitates interest, focus, and serenity around the musical objects as other museums can do around the work of visual artists. It was striking how a large group of people could be in one place learning about Cecil Taylor, and not in a performance venue listening to a concert. The space and presentation lent a dimension to Taylor’s work that seemed essential; a defined environment, surrounded by interested public, with enough physical space to explore the elements without feeling rushed. Curiosity was required, the act of walking up to something rather than having it be presented without warning completed the aesthetic transaction between listener and composer, the physical grandness of the space and the commitment needed to walk to each new corner seemed to make accessible even elements of Taylor’s output that seem to defy it. Several leather couches were placed overlooking windows, where one could put on provided headphones and listen to selected albums. The couch that chose me was playing Taylor’s first recording as a leader, Jazz Advance. I sat uninterrupted listening to his performance of “Bemsha Swing” mesmerized by his improvisation, while the north view of 10th avenue lay before me. In the context of the exhibit the recording was hypnotizing, energizing and seemed to draw one into the sound and into one’s self.

Several leather couches were placed overlooking windows, where one could put on provided headphones and listen to selected albums. The couch that chose me was playing Taylor’s first recording as a leader, Jazz Advance. I sat uninterrupted listening to his performance of “Bemsha Swing” mesmerized by his improvisation, while the north view of 10th avenue lay before me. In the context of the exhibit the recording was hypnotizing, energizing and seemed to draw one into the sound and into one’s self. It is a shame this display could not be made permanent. What a wonderful monument to the original free jazz pioneer, and one that restored (or perhaps reinvented) a place suitable for the expansiveness of his output. Every great musician should have such a place, perhaps the time has come for Music museums to arise along side those dedicated to Art.

It is a shame this display could not be made permanent. What a wonderful monument to the original free jazz pioneer, and one that restored (or perhaps reinvented) a place suitable for the expansiveness of his output. Every great musician should have such a place, perhaps the time has come for Music museums to arise along side those dedicated to Art.